Throughout history, Christians have employed symbols and Christograms as profound expressions of their faith, enabling them to convey complex spiritual truths in accessible and impactful ways. These visual representations, ranging from the iconic cross to the intertwined Greek letters Chi and Rho, served not only as identifiers for early believers facing persecution but also as powerful reminders of key theological concepts and events. By integrating symbols into worship, art, and daily life, Christians have created a rich tapestry of visual language that deepens their spiritual experience and fosters a sense of community. In an age where words can sometimes fail to capture the essence of faith, these symbols continue to inspire and unite believers around shared beliefs and traditions.

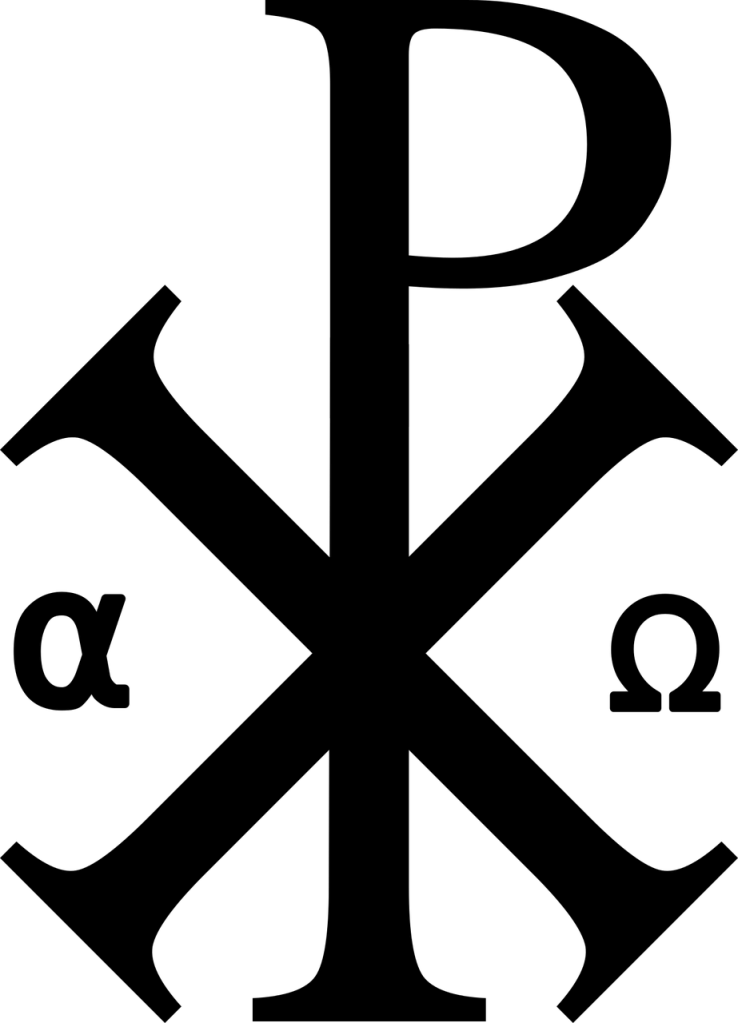

Chi-Rho Monogram (XP)

The Chi-Rho Monogram is commonly known as a Christogram. A Christogram is a symbol or combination of letters that abbreviates the name of Jesus Christ. It serves as a religious emblem representing Christ, Christianity, and Christians.

Although the two letters resemble X and P in the English alphabet, they are actually derived from the Greek alphabet. The letters X and P are frequently used as symbols for Christ. The first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek are X and P. In the Greek alphabet, X corresponds to ‘CH’ (pronounced ‘Kye’), while P stands for ‘R’ (pronounced ‘Roe’). This is why it’s called the Chi-Rho Monogram.

The letters XP signify Christ. The letter “α” represents alpha, the first character of the Greek alphabet, while “Ω” represents omega, the last character. In the Book of Revelation, Jesus is called the Alpha and the Omega (Revelation 1:8, 21:6, and 22:13). This concept illustrates that Jesus is both the beginning and the end of all things. Highlighting His eternal nature includes His presence at the creation of the world and His role at the end of times, which reinforces the belief in His divinity and authority.

The Chi-Rho holds significance for its religious connotation and because Emperor Constantine (the first Roman emperor to embrace Christianity) utilised it as a military standard in the early 4th century. This marked a crucial moment in the history of Christianity as it became more broadly accepted throughout the Roman Empire. Today, the Chi-Rho remains a strong symbol of the Christian faith.

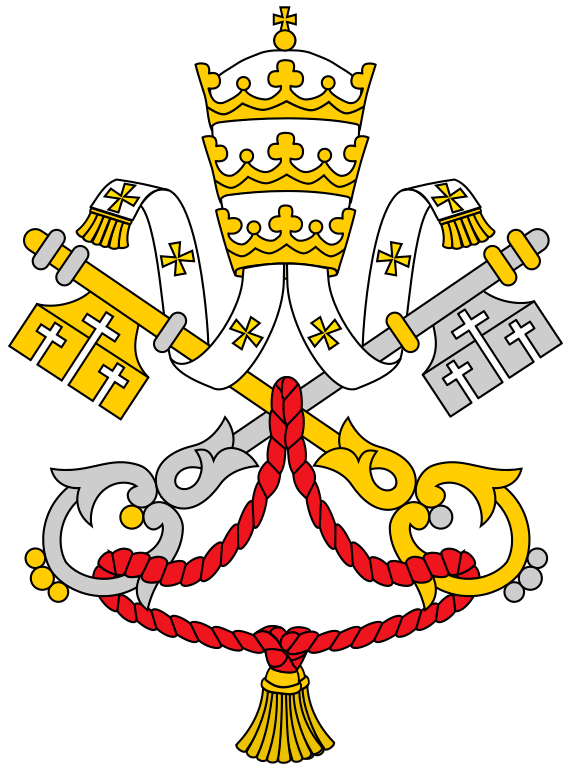

Coat of Arms of the Holy See

The emblem of the Holy See features a pair of crossed keys and a papal tiara connected by a red cord. Its roots can be traced back to the early Middle Ages. Nevertheless, the particular designs, including crossed keys and papal tiara, became more standardised in the 14th century.

The Holy See refers to the main governing body of the Catholic Church, led by the Pope. It is recognised as a sovereign entity with jurisdiction, diplomatic relations, and global presence. The phrase “Holy See” is commonly used to denote both the ecclesiastical authority of the Pope and the administrative framework that underpins Vatican City.

Crown of Thorns

A wreath made from thorny branches was placed on Jesus’ head as a crown to mock Him as a king and to inflict pain and humiliation during His crucifixion. The specific type of plant is not mentioned in the biblical texts. One probability is that it was made from an Egyptian thorn bush or a similar species.

“Then the soldiers of the governor took Jesus into the praetorium, and they gathered the whole battalion before him. And they stripped him and put a scarlet robe upon him, and plaiting a crown of thorns they put it on his head, and put a reed in his right hand. And kneeling before him they mocked him, saying, “Hail, King of the Jews!’”

Matthew 27:27-29

Bishop’s Staff (Crozier)

A bishop’s staff, also known as a crozier, is a ceremonial staff that is shaped like a Shepard’s staff, carried by bishops in the Catholic Church.

The crozier symbolises the bishop’s role as a shepherd of his flock, reflecting his duty to guide, nurture, and protect the faithful. It also signifies the authority of the bishop within the Church, representing his leadership and responsibilities in teaching and governance.

The crozier emphasises the spiritual mission of the bishop to lead his diocese in faith, worship, and service. This is emphasised by the crozier typically having a curved top, resembling a shepherd’s staff, which reinforces the imagery of shepherding. It is often elaborately designed and can be made from various materials, including wood, metal, or a combination of both.

Bishops carry the crozier during liturgical ceremonies, such as ordinations, confirmations, and other significant events. It is a visible sign of their office and is usually placed beside the bishop’s throne or altar when not in use.

“The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want;

he makes me lie down in green pastures.

He leads me beside still waters;

he restores my soul.

He leads me in paths of righteousness

for his name’s sake.”

Psalm 23: 1-3

Crux

The cross, a fundamental symbol of Christianity, is often referred to in contemporary contexts as a crucifix, which typically features a depiction of Jesus Christ. Historically, before the inception of Christianity, this significant symbol was known as a “Crux,” deriving from the Latin term for cross.

The crux primarily described an execution method that involved binding or nailing the condemned person to a large wooden cross, beam, or stake, then leaving them to die. The Roman Empire, especially, practiced this execution method, known as crucifixion, as early as the 6th century BC. Slaves, thieves, and rebels were the primary targets of this punishment. The crux functioned as a harsh form of capital punishment, symbolising suffering and disgrace. The act of crucifixion aimed to serve as a public warning, showcasing the state’s power.

The crux usually consisted of several components, which include the following:

Patibulum: Refers to the horizontal beam of the crux to which the condemned person’s arms were attached.

Stipes: This term denotes the vertical post of the crux embedded in the ground.

Titulus: This was a placard or sign indicating the condemner’s name and the charges against them.

Crurifragium: This describes the practice of breaking the legs of a crucified individual to hasten death, which did not occur during Jesus’ crucifixion.

Over time, the term “crux” has become less common concerning executions but is now used to describe the central or most vital aspect of a discussion, often highlighting the core point being addressed. “The crux of the issue.” This application has changed over time, yet its historical connection to execution remains essential, particularly in conversations about its subsequent Christian implications.

Dove With Leaf

The dove represents the Holy Spirit, especially as seen during the baptism of Jesus when the Spirit descended like a dove. The olive leaf signifies peace and hope; its origins trace back to the story of Noah’s Ark, where a dove brought back an olive branch to show that the floodwaters had receded. Together, they symbolise the peace and renewal offered through the Holy Spirit and the promise of salvation in Christian belief.

“Then he sent out the dove from him, to see if the waters had subsided from the face of the ground; but the dove found no place to set its foot, and it returned to him to the ark, for the waters were still on the face of the whole earth. So he put out his hand and took it and brought it into the ark with him. He waited another seven days, and again he sent out the dove from the ark; and the dove came back to him in the evening, and there in its beak was a freshly plucked olive leaf; so Noah knew that the waters had subsided from the earth.

Genesis 8: 8-11

“And John testified, “I saw the Spirit descending from heaven like a dove, and it remained on him.’”

John 1: 32

Celtic High Cross

A Celtic high cross, also referred to as a standing cross (Irish: crois ard or ardchrois), is a large, often intricately carved stone cross that originated in Ireland and other parts of the British Isles during the early Middle Ages (8th–12th centuries). It is characterised by its distinctive shape, featuring a ring or circle around the intersection of the arms and stems, symbolising eternity and unity.

Detailed biblical scenes, intricate Celtic knotwork, and other symbolic designs often adorned these crosses, serving as both religious monuments and teaching tools for sharing Christian stories. Found near churches, monasteries, and sacred sites, high crosses reflect the blending of Christian faith with Celtic artistic traditions, representing a rich cultural and spiritual heritage.

Ichthys

The Ichthys, often represented by a simple fish symbol, is an early Christian emblem. The term “Ichthys” is derived from the Greek word for fish (ἰχθύς) and is an acronym for “Iēsous Christos Theou Yios Sōtēr,” which translates to “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.” This symbol was used by early Christians to identify themselves and their faith discreetly, especially during periods of persecution. It remains a popular symbol of Christianity today.

Additionally, Jesus is often referred to in the context of fishing. He called his disciples, many of whom were fishermen, to become “fishers of men” (Matthew 4:19). The act of feeding the five thousand with fish and loaves (John 6:1-14) also highlights the significance of fish in His ministry.

“And he said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.’”

Matthew 4:19

“There is a lad here who has five barley loaves and two fish; but what are they among so many?” Jesus said, “Make the people sit down.” Now there was much grass in the place; so the men sat down, in number about five thousand. Jesus then took the loaves, and when he had given thanks, he distributed them to those who were seated; so also the fish, as much as they wanted. And when they had eaten their fill, he told his disciples, “Gather up the fragments left over, that nothing may be lost.’”

John 6: 9-12

IHS (IHC/JHS)

IHS is a Christian monogram that signifies the name of Jesus Christ. It originates from the first three letters of “Jesus” in Greek: ΙΗΣΟΥΣ (Iēsous). The letters “IHS” frequently appear in Christian art and worship, symbolising Christ and highlighting His divinity and role in salvation. Throughout history, the monogram has been interpreted in various manners, including “Iesus Hominum Salvator,” which means “Jesus, Saviour of Men.”

On the other hand, IHC is another version of Jesus’ name that utilises the first letters from the Greek spelling. It is commonly regarded as an alternative abbreviation for IHS, based on the Greek letters after being converted into Latin.

Another version is JHS, which comes from the first three letters of “Jesus” in both Greek and Latin. It is often understood as representing “Iesus Hominum Salvator,” meaning “Jesus, Saviour of Men.” Similar to IHS, JHS is featured in Christian art and worship.

IHS, IHC, and JHS act as symbols of Christ and illustrate His importance in Christianity, particularly in Catholicism, where they can be seen on altars, vestments, and in various religious settings, serving as a reminder of Jesus’ central role in the Christian faith.

Iota Chi (IX)

In Christianity, Iota Chi (ΙΧ) stands for the initial letters of “Jesus Christ” in Greek: “Iota” (Ι) representing “Iesous” (Jesus) and “Chi” (Χ) representing “Christos” (Christ). This abbreviation is frequently utilised in Christian art and symbolism, often appearing in churches and sacred writings. The significance of ΙΧ lies in its expression of faith and respect for Jesus Christ within the Christian faith. It highlights the importance of Christ in the belief system and serves as a reminder of His role in salvation.

Lamb of God

The lamb is primarily associated with Jesus Christ, often called the “Lamb of God.” This title emphasises His role as the sacrifice for humanity’s sins. It is founded on the imagery of the Passover lamb from the Old Testament, which was slain to save the Israelites from death during the Exodus. In the New Testament, John the Baptist identifies Jesus as the Lamb of God in the Gospel according to John (John 1:29), highlighting Jesus’s mission to save humanity through His death and resurrection. The lamb symbolises innocence, purity, and the ultimate sacrifice, which are critical concepts in the Christian faith. Furthermore, Jesus refers to lambs throughout the Gospels to express profound theological and pastoral messages during His ministry.

“The next day he saw Jesus coming toward him and declared, “Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!’”

John 1:29

“‘I am the good shepherd; I know my own and my own know me, as the Father knows me and I know the Father; and I lay down my life for the sheep. And I have other sheep, that are not of this fold; I must bring them also, and they will heed my voice. So there shall be one flock, one shepherd. For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life, that I may take it again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again; this charge I have received from my Father.’”

John 10:14-18

“‘What do you think? If a man has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the hills and go in search of the one that went astray? And if he finds it, truly, I say to you, he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray. So it is not the will of my Father who is in heaven that one of these little ones should perish.’”

Matthew 18:12-14

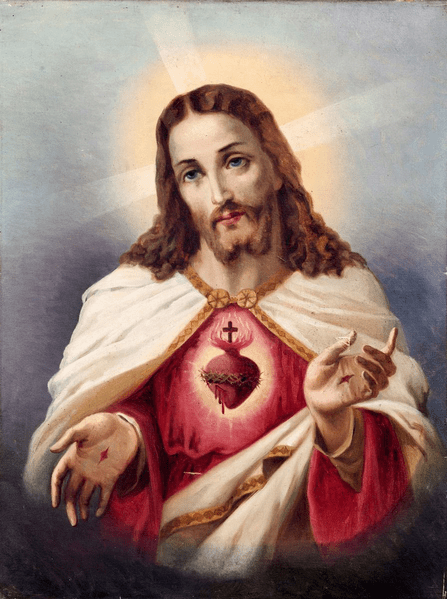

Sacred Heart

The Sacred Heart of Jesus represents His immense love for humanity. This devotion highlights Jesus’ physical heart as a symbol of His compassion and the selfless love He demonstrated through His suffering, death, and resurrection.

The Sacred Heart is often depicted as a radiant heart that emits divine light, featuring a wound from a lance to symbolise Jesus’ sacrifice during the crucifixion; a crown of thorns, representing his suffering and humiliation; a cross, signifying his ultimate act of love and victory over sin; and bleeding, which symbolises the redemption and grace offered through his sacrifice. Sometimes, the image portrays the heart glowing within Christ’s chest, with His wounded hands gesturing towards it. His hands were injured from being nailed to the cross during his crucifixion. Together, these elements highlight Christ’s profound love and compassion for humanity.

Serpent and Apple

The serpent and apple primarily represent temptation, sin, loss of innocence and Original Sin. The serpent, often associated with Satan, deceives Eve into eating the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, which God prohibited. This act symbolises disobedience to God’s command and introduces sin into the world, leading to humanity’s fall.

The apple, while not specifically mentioned in the Bible, has become a widely recognised symbol of the fruit that represents knowledge and the consequences of seeking it outside of God’s will. This story underscores the concepts of free will, moral choice, and the need for redemption through Jesus Christ.

Some Catholic statues traditionally feature serpent and apple imagery beneath their feet, commonly associated with the Virgin Mary, especially in depictions of her crushing the serpent. This image has deep theological and biblical roots tied to the concept of Mary’s victory over sin and evil, particularly through the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception.

“Now the serpent was more crafty than any other wild animal that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, “Did God say, ‘You shall not eat from any tree in the garden’?” The woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the middle of the garden, nor shall you touch it, or you shall die.’” But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves.”

Genesis 3: 1-7

Shamrock

The shamrock is widely recognised as a symbol of St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland. As the story goes, St. Patrick used the three-leafed shamrock to illustrate the idea of the Holy Trinity, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, to the Irish. Each leaf represents a part of the Trinity, while the entire plant signifies their unity. This association has turned the shamrock into a symbol of Irish culture and Christian belief. It is thought that St. Patrick came to Ireland around 432 AD.

Triquetra (Irish Trinity Knot)

The Triquetra or Irish Trinity Knot, is often associated with various interpretations, including the Christian Holy Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). However, its origins predate Christianity and are rooted in Celtic culture, symbolising concepts like the interconnectedness of life, nature, and the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. So, while it can represent the Trinity in a Christian context, its meanings are broader and can vary based on cultural interpretations.

The triquetra is from the Latin adjective triquetrus, “three-cornered”, and is a triangular figure composed of three interlaced arcs or (equivalently) three overlapping vesicae piscis lens shapes. It is used as an ornamental design in architecture and medieval manuscript illumination (particularly in the Insular tradition). Its depiction as interlaced is common in Insular ornaments from about the 7th century.

Today in Ireland, the Irish Trinity Knot is often a design element in popular Irish jewellery such as Claddaghs.