Jesus Christ, a central figure in history and the Christian faith, lived during a time of profound cultural, political, and spiritual complexity in the Roman-Judaean world. Born into a Jewish family in the Roman-occupied province of Judaea, the dual influences of the ancient faith of Judaism and Roman governance shaped Jesus’ life and teachings.

These two cultures coexisted, sometimes uneasily, with the dominant culture of Rome and its Hellenistic influences, and Judaism was at the crossroads of civilisations. The following page explores in detail the time Jesus came from, highlighting the social, political, and cultural complexities that shaped his life and teachings.

Where Did Jesus Come From?

Jesus of Galilee

Jesus came from Galilee, a region in the northeastern part of the Roman province of Judaea, which was itself located on the empire’s eastern frontier. Caesarea Maritima became the capital city of Judaea after the Roman Empire took full control of the region. Jerusalem continued to serve as the religious and cultural hub for the Jewish community

Galilee was part of a client kingdom under the rule of Herod Antipas, a Tetrarch (meaning “ruler of a quarter”), who governed under Roman oversight. This region lay near key trade routes connecting the Mediterranean (Southern Europe and North Africa) to the Middle East, making it a cultural crossroads influenced by both Roman and Hellenistic traditions.

Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus was raised in the small, modest, rural, Galilean village of Nazareth. The village, estimated to have a population of 100–500 people, primarily engaged in farming and handicrafts.

Due to the town’s poor social standing, its well-known neighbours frequently ignored it and thought it was unimportant. For instance, Nathanael famously poses the question, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” in the Gospel of John.

“Nathanael said to him, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” Philip said to him, “Come and see.’”

John 1:46

Climate

Judaea was characterised as having a Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. The coastal regions, like Caesarea Maritima, had a more temperate climate, benefiting from sea breezes that moderated the heat. In contrast, the interior regions, including Jerusalem, were more prone to extreme temperature fluctuations, with cold winters that could occasionally bring snow, and hot, dry summers.

The deserts to the east experienced harsher conditions, with extremely hot summers and very little rainfall. This variation in climate across different regions influenced agricultural practices, with the fertile coastal plains and valleys supporting crops like wheat, barley, and olives, while the harsher desert areas were less conducive to farming.

Despite these challenges, the climate allowed for a range of activities such as agriculture, trade, and religious rituals, which were integral to life in Judaea under Roman rule.

Political Governance

The Herodian Tetrarchs

During Jesus’ time, the political governance of the Roman province of Judaea was a complex system involving both Roman prefects (governors who worked under the Roman Empire) and local Herodian rulers (related to Herod the Great and his dynasty). After the death of Herod the Great in 4 BC, his kingdom was divided among his sons, with Herod Antipas ruling Galilee as Tetrarch under Roman oversight.

The Roman Prefects

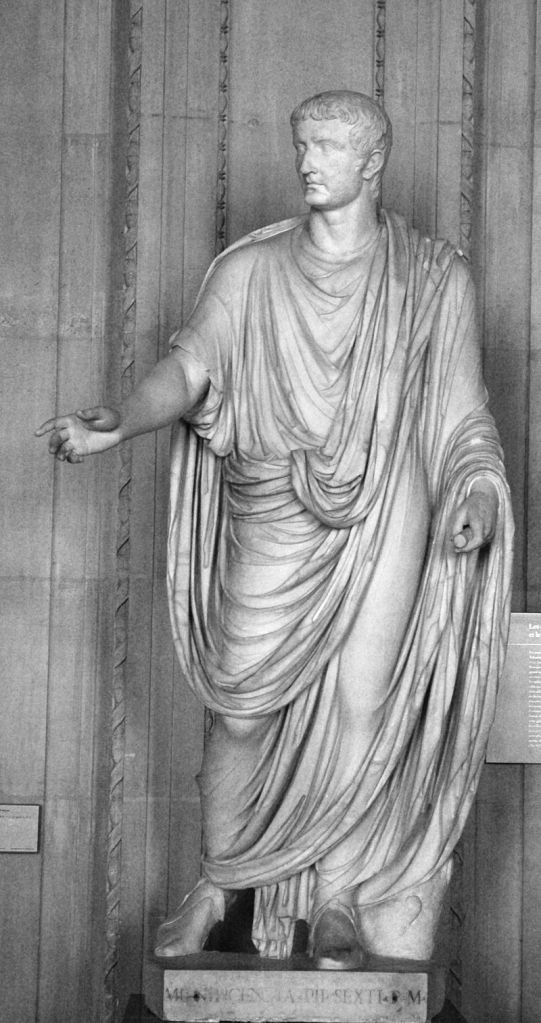

During Jesus’ ministry, the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate (reigned 26–36 AD) ruled the province of Judaea, exercising supreme authority over law, order, and military matters, reporting to the Roman governor of Syria. The emperor of Rome at the time of Pilate was Tiberius Caesar Augustus, commonly known as Tiberius (reigned from 14-37 AD), succeeding Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Pilate’s role was to maintain peace and ensure Roman interests, which often put him at odds with Jewish leaders.

The Jewish Sanhedrin

Local governance also included the Sanhedrin, a Jewish council of religious leaders, which had authority over religious and some civil matters within the Jewish community, particularly in Jerusalem. Though the Sanhedrin could enforce religious law, they were limited by Roman authority in political matters. The Sanhedrin played a key role in the trial of Jesus, bringing him before Pilate for sentencing after accusing him of blasphemy and claiming to be a king, thus challenging Roman rule.

This complex power structure, with overlapping Roman and local authority, created tensions that contributed to the political and religious dynamics surrounding Jesus’ ministry and crucifixion.

Jesus’ Nationality and Political Status

Jesus’ nationality can be described as “Roman-Judaean” because he was born in Bethlehem, a town in Judaea, a province that was under Roman occupation at the time. Politically, this made Jesus a subject of the Roman Empire, living under Roman imperial control, though he did not possess full Roman citizenship, which was a privilege that could only be acquired through specific means, such as military service, special grants from the emperor, or by birth in a Roman family or city.

His Judaean identity, however, was central to his cultural and religious life, as he was born into a Jewish family and adhered to the faith’s customs and beliefs. The term “Roman-Judaean” thus encapsulates his dual identity, as he existed within the framework of Roman rule and his deep ties to the Judaean people and their religious traditions, which were at the heart of his mission and teachings. This blending of Roman political authority and Jewish cultural heritage shaped much of his life and context in the ancient world.

Economy and Currency

The Judaean economy during the period of Roman rule (63 BC – 135 AD) was primarily agrarian, with agriculture serving as the economic backbone, producing crops like wheat, barley, olives, and grapes.

Trade, both regional and international, played a significant role, with Judaean ports like Caesarea facilitating commerce with the Mediterranean and beyond. The economy was also heavily influenced by Roman taxation, which was burdensome and often outsourced to local elites or Roman tax collectors, leading to widespread social unrest.

Economic disparities were marked by the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few elites, while the majority of the population faced economic hardship. Despite these challenges, Judaea was an integral part of the Roman Empire’s broader economic system, balancing local traditions with Roman economic policies.

Caesarea Maritima – The Administrative Capital of Judaea

Caesarea Maritima, an ancient and medieval port city built by Herod the Great and named in honour of Caesar Augustus, was the economic and administrative powerhouse of Roman-Judaea.

As the region’s primary port city on the Mediterranean, it facilitated extensive trade with the wider Roman Empire, exporting agricultural products like olive oil, wine, and dates while importing luxury goods and essential items. Its sophisticated harbour, Sebastos, supported large-scale shipping and attracted merchants, sailors, and traders, making it a thriving commercial hub.

Caesarea also served as the administrative capital of Judaea, housing the Roman governor and his staff, which brought additional economic activity through governance, taxation, and the presence of Roman soldiers. With its advanced infrastructure, including aqueducts and public buildings, Caesarea was a linchpin of economic and political life in Roman-Judaea.

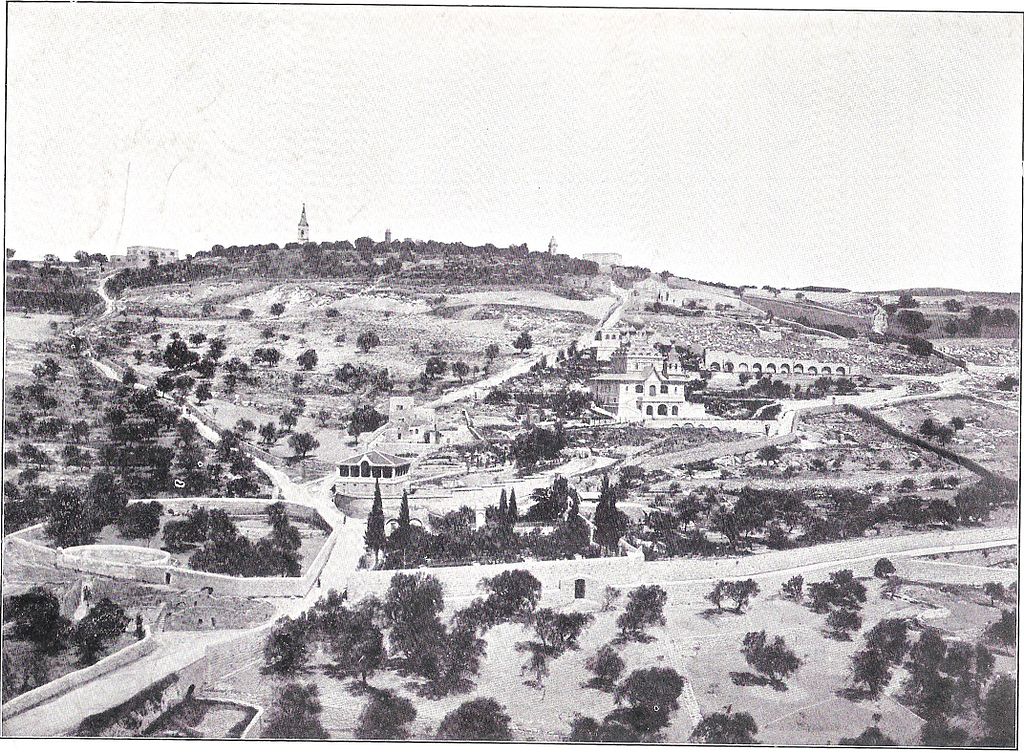

Jerusalem – The Religious Capital of Judaism Within Judaea

Other cities, such as Jerusalem, served as the religious centre of Roman-Judaea, with the Second Temple significantly influencing their economy. The Second Temple, also known as Herod’s Temple, was the second major temple built for Jewish worship in Jerusalem, replacing the First Temple (Solomon’s Temple), which had been destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC. The Second Temple was constructed starting around 516 BC and stood until its destruction by the Romans in 70 AD. It was effectively the Jewish (Judaism) equivalent of present-day Vatican City for Catholics (Catholicism).

The Temple attracted vast numbers of Jewish pilgrims from across Judaea and the wider Roman Empire, generating revenue through offerings, sacrifices, and the annual Temple tax. These activities supported a large workforce, including priests, merchants, artisans, and labourers, and spurred demand for goods and services such as food, lodging, and animals in exchange for sacrifice.

Additionally, Jerusalem was a political and administrative hub, hosting Roman officials and local elites, which further boosted its role as a centre for trade and economic activity. The city’s unique religious importance made it a vital economic contributor to the region.

Jesus The Carpenter

Jesus was classified as a tekton (τέκτων), Greek for skilled labourer, as he is often described as a carpenter in the Bible. This positioned him within the Roman-Judaean economy as part of the artisan class, serving both rural and urban communities. Artists like Jesus provided essential services by crafting tools, repairing structures, and participating in construction projects, particularly in growing urban centres like nearby Sepphoris, which saw significant development under Roman influence.

While artisans held a modest social status, their work connected them to both peasant farmers and wealthier urban clients, offering some economic mobility but also exposing them to the instability of irregular work under the burdens of Roman taxation and widespread inequality. Jesus’ background as a tekton likely informed his empathy for the poor and his critique of systemic exploitation, shaping the socio-economic themes central to his ministry.

Roman-Judaean Coins

Roman currency was based on a system of coins made from gold, silver, and bronze, with the denarius being the most commonly used silver coin, alongside other denominations like the sestertius (bronze) and aureus (gold). These coins were used for trade, taxation, and imperial propaganda, and over time, their value fluctuated due to economic pressures, leading to inflation and devaluation in the later years of the Roman Empire.

Coins minted during the Roman occupation of Judaea often depicted Roman emperors, but some, particularly from the First Jewish Revolt (66–73 AD), featured Jewish symbols such as the Temple menorah and the palm tree, expressing Jewish identity under Roman rule.

Languages

Judaea was a multilingual environment. The region’s population spoke several languages due to its geographical location in the Middle East, which was near North Africa and Mediterranean Europe, and its cultural and political context. In Jesus’ time, the primary languages spoken in the province included the following:

Aramaic

During Jesus’ time, Aramaic was the predominant spoken language in Judaea and the surrounding regions. After the conquests of the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires (911 BC – 609 BC), it became a widely used Semitic language across the Middle East, replacing earlier languages like Hebrew in everyday communication. Aramaic was the main language Jesus spoke in His day-to-day life.

Jewish life, culture, and religion at the time heavily relied on this language, with portions of the New Testament, including some of Jesus’ sayings, believed to have originated in Aramaic before translation into Greek. Both daily conversation and religious settings, such as synagogue worship and teachings, commonly used Aramaic.

Hebrew

During Jesus’ time, Hebrew was primarily a liturgical and literary language, rather than a widely spoken one in everyday life. While Aramaic was the common spoken language in Judaea, Hebrew retained its importance as the language of religious texts and Jewish law. The Hebrew Bible and key religious writings were composed in Hebrew.

In the 1st century AD, many Jews, especially those in religious leadership, would have been familiar with Hebrew for reading the scriptures and conducting religious ceremonies, though it was often read in conjunction with Aramaic translations, which made the texts more accessible to the general population. Hebrew’s role as a spoken language had diminished, but it remained central to Jewish identity and religious practice.

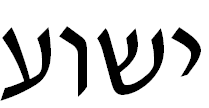

The word “Yeshua” is the Hebrew name for Jesus, which means ‘the Lord saves,’ and it’s the name people called Him when He lived on Earth.

Latin

During Jesus’ time, Latin was the official language of the Roman Empire, which ruled over Judaea. The local population did not speak Latin widely, but Roman administration, law, and military relied heavily on it. Roman soldiers, governors, and officials used Latin for official matters, such as legal documents and decrees and in interactions with local leaders. Roman-controlled urban areas and dealings with the occupying Roman authorities in Judaea would have presented opportunities to encounter Latin.

Although the Jewish people primarily spoke Aramaic and Hebrew, Latin played a significant role in the political and military presence of the Roman Empire in the region. Additionally, the New Testament uses Latin in official Roman contexts, as evidenced by the inscription on Jesus’ cross (“Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”).

Greek

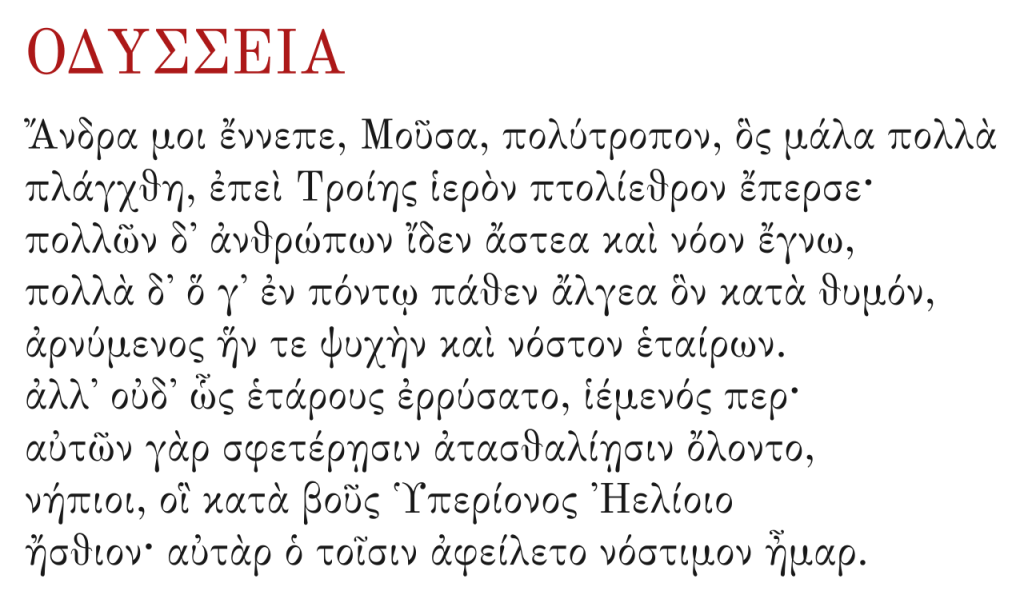

The Greek, also known as Hellenistic, influence that began with Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BC led to the widespread use of Greek as the lingua franca throughout the eastern Mediterranean, including Judaea, during Jesus’ time. Greek was the language of commerce, intellectual discourse, and administration across the Roman Empire, particularly in urban centres and among the educated elite. Although the common people in Judaea spoke Aramaic, many Jews, especially those living in larger cities or who had contact with Greek-speaking cultures, were familiar with Greek.

The New Testament itself was written in Greek, reflecting its widespread use among early Christian communities, as well as the influence of Greek thought and culture on the region. The Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, was popular among diaspora Jews.

Religion

Roman-Judaean religion during the time of Jesus was marked by the coexistence of Jewish monotheism and Roman polytheism, which created significant cultural and religious tensions.

Abrahamic Judaism

Judaism, a monotheistic religion, centred on the covenant between Abraham, his descendants and God to adhere to His laws. Jesus was born and raised with this faith.

Jewish religious life was governed by the Torah (Hebrew Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), and interpreted by various sects, including the Pharisees, who focused on the oral traditions and laws, and the Sadducees, who were linked to the priestly class and the Temple. The Temple in Jerusalem served as the central hub of religious activities, observing rituals, sacrifices, and festivals like Passover.

Jews in Judaea practiced their faith through regular synagogue worship, observance of the Sabbath, and participation in annual festivals such as Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot. The Jerusalem Temple was the heart of religious life, where sacrifices were made, and the priesthood played a key role in rituals. Jewish laws and customs, including dietary restrictions (kosher laws), circumcision, and purity rituals, shaped daily life. Despite Roman control, Jews in Judaea maintained a strong sense of identity, with the Sanhedrin serving as the governing body for religious matters.

Greco-Roman Paganism

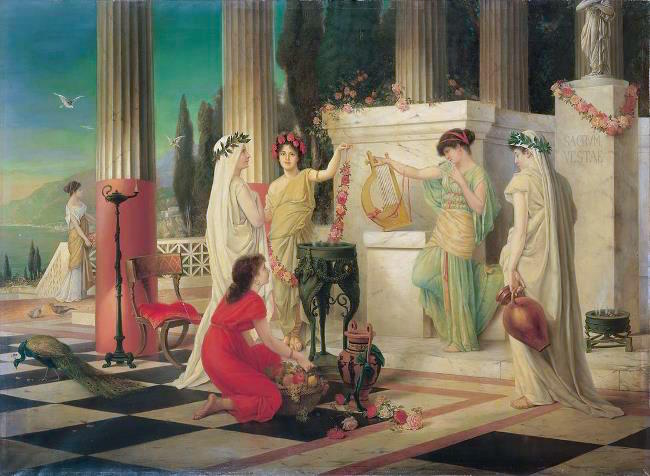

In contrast, the Romans practiced a polytheistic religion, which was characterised by the worship of a vast pantheon of gods and the practice of state-sponsored rituals and ceremonies aimed at maintaining the favour of the gods. Particularly non-Jewish Romans in Judaea engaged in polytheistic worship, paying homage to deities such as Jupiter, Mars, and Venus, and frequently revered the emperor as a god, particularly after his death.

Roman religious life revolved around temples, sacrifices, and festivals, incorporating many local deities into their practices through syncretism (the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought).

The Romans adopted much of Greek (Hellenistic) mythology, integrating Greek gods into their own pantheon but giving them Latin names and adapting their worship to fit Roman values and society.

Cultural, Political and Religious Conflicts

Romans generally allowed conquered peoples to practice their own religions, but tensions arose when the Roman authorities, such as under Emperor Caligula, tried to impose imperial cult worship on the Jews. This clash between Jewish monotheism and Roman pagan religious practices contributed to political unrest, as many Jews, including violent separatist groups like the Zealots, sought to resist Roman influence and restore Jewish independence, leading to occasional uprisings and conflict, such as the Jewish revolt in 66 AD.

The religious climate was further complicated by messianic hopes, as many Jews awaited a saviour to deliver them from Roman oppression, which made Jesus’ message of a spiritual kingdom a provocative and controversial stance.

Family Structures and Marriages

The family structure in Roman-Judaean society was rooted in patriarchal traditions, but attitudes and traditions differed significantly between the Roman and Jewish cultures.

Roman Households

In Rome, the paterfamilias (the male head of a Roman family) wielded significant legal power, including control over property, marriage arrangements, and even the lives of family members.

Roman women, especially those of higher status, had more legal rights than their Jewish counterparts, such as owning property and engaging in public affairs. The Roman family could be more fluid, with marriage and divorce being relatively common, and women sometimes played roles in public religious rituals and civic life.

Roman Attitudes Towards Marriage

Polygamy was legal in earlier Roman history but largely phased out by the time of the empire. During the time of Jesus, Roman marriages were typically monogamous, although it was more common for Roman men, especially the elite, to engage in extramarital affairs with concubines or slaves. Relationships outside of marriage were not considered morally reprehensible, as long as they did not disrupt familial duties or cause public scandal. Over time, especially with the spread of Christianity under Rome’s first Christian emperor, Constantine the Great (306 to 337 AD), these attitudes changed, generally condemning extramarital relationships.

Roman attitudes toward families in Roman Judaea often emphasised public status and individual rights; family dynamics were more secular, influenced by Hellenistic culture and Roman law.

Jewish Households

In contrast, Jewish family structure was deeply intertwined with religious laws and customs. The father’s role was also central, but the family was primarily governed by religious observances and the laws of the Torah, which shaped everyday life.

Jewish women, while respected, had a more domestic role focused on child-rearing, maintaining the home, and upholding religious practices. Divorce was rare and strongly discouraged, with family unity being crucial for preserving religious identity. Jewish families placed great importance on community and religious tradition, especially in maintaining rituals like Sabbath observance, circumcision, and participation in key religious festivals.

Social attitudes in these communities were more conservative, with a strong emphasis on communal ties, religious purity, and the maintenance of cultural practices in the face of Roman influence.

The key difference between Roman and Jewish family life lay in the Roman focus on individual rights and social flexibility, versus the Jewish focus on religious duty, family cohesion, and communal identity, which created a clear cultural divide.

Jewish Attitudes Towards Marriage

Jewish marriages were strictly monogamous according to Jewish law, as outlined in the Torah. Extramarital relationships were generally condemned. According to the Torah (e.g., Leviticus 20:10), the punishment for adultery could be death by stoning for both the man and woman involved. An example of this during Jesus’ ministry was the story of the woman caught in adultery is one of the most well-known moments in the New Testament where a woman caught in adultery is brought before Jesus. The accusers remind Jesus that, according to the Law of Moses, such an act should be punished by stoning. However, Jesus famously responds:

“Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.”

John 8:7

By the Roman period, such punishments were rarely carried out due to Roman oversight and restrictions on Jewish legal authority. While polygamy had existed in earlier periods of Jewish history, by the time of the Roman occupation, it had become rare and was not widely practiced in Judaea.

Funerals

Funerals in Roman-Judaea reflected the cultural blend of Roman and Jewish traditions, with significant differences between the two. The differences between the two practices underscored the religious and cultural distinctions between Romans and Jews, even as their societies intersected under Roman rule.

Jewish Funerals

Upon death, the body was washed and anointed with spices, such as myrrh and aloe, to prepare it for burial, in line with the customs described in the Hebrew Scriptures. Burial typically occurred on the same day as death, often outside the city in family tombs or cave tombs, with the body placed in a stone or clay ossuary, especially for wealthier families.

A funeral procession would accompany the body, and mourners would often lament loudly, expressing grief. The practice of sitting shivah, a seven-day mourning period, was observed by the immediate family, during which they refrained from work and received visitors who offered comfort.

Burial rituals also included prayers and blessings, and the body would be covered with a plain cloth, avoiding elaborate funerary rites associated with other cultures. These practices reflected a deep commitment to honouring the deceased in accordance with Jewish law and tradition, while maintaining a focus on the sanctity of life and the hope of resurrection.

Roman Funerals

On the other hand, Roman funerals, particularly for the elite, were often more elaborate. Upon death, the body was prepared by family members, washed, anointed with oils, and dressed in a toga or simple garments, reflecting the individual’s status. The deceased was usually laid out in the home, where mourners would gather to pay respects.

A funeral procession, often accompanied by music, professional mourners, and incense, would lead the body to the burial site, which could include a tomb, cremation pyre, or family mausoleum. Roman funerals emphasised the concept of imperium (authority), and public figures or wealthy individuals often had monuments or inscriptions commemorating their lives. Burial sites were typically located outside city walls, and the wealthy might have elaborate tombs, sometimes with sculptures or reliefs depicting the deceased.

Roman funerary practices in Judaea might blend these customs with local traditions, especially in predominantly Jewish areas, where they avoided cremation out of respect for local beliefs. Over time, burial became more common, especially with the spread of Christianity, which viewed the preservation of the body as important for resurrection.

Entertainment

Urban Forms of Entertainment

Urban centres in cities like Jerusalem and Caesarea Maritima, under Roman influence, introduced gladiatorial games, chariot races, and Roman theatre performances, often held in amphitheatres or public arenas, though these were more popular among Roman and Hellenistic elites. Roman leisure generally aimed to celebrate Roman deities, foster civic unity and imperial ideology.

Jewish Distain for Roman Entertainment

Jewish customs, deeply rooted in religious observance, often clashed with these forms of entertainment, leading many Jews to view such Roman-style spectacles with disdain, considering them morally corrupting and contrary to religious values.

Jewish ethics, deeply rooted in religious observance and law, frequently condemned Roman entertainment because it was associated with idolatry, pagan rituals, and violent displays. In particular, the Jewish faith clashed with Roman traditions like gladiatorial games, where skilled fighters, known as gladiators, engaged in combat until death or surrender. These practices were seen as morally reprehensible because they were seen as a glorification of death and disregard of the sanctity of life, an important tenet of Judaism as stated in the Ten Commandments in Exodus of the Hebrew Bible.

“You shall not kill.

Exodus 20:13

Rural Forms of Entertainment

In rural areas and Jewish communities, entertainment was more community-based, centred around feasts, weddings, religious festivals like Passover, and storytelling. Music and dance were often part of these events, along with public gatherings in the marketplace. Traditional Jewish forms of entertainment focused on communal worship, prayer, and celebrating religious holidays, offering a contrast to the Roman emphasis on physical spectacles and luxury. Thus, the entertainment landscape in Roman Judaea was marked by a blend of Roman-inspired public amusements and more modest, faith-driven celebrations.

Art

Roman-Judaean art was shaped by both Roman influence and Jewish cultural traditions. Some notable examples include:

The Arch of Titus

Although not in Judaea, this Roman monument, located in Rome, Italy, celebrates the conquest of Jerusalem in 70 AD, features reliefs depicting Roman soldiers carrying the Menorah (seven-branched candelabrum) from the Temple in Jerusalem, symbolising the integration of Judaea into the Roman Empire.

Jewish Mosaics

Found in synagogues (Jewish temples of worship), these often-featured geometric patterns, animals, and symbols like the Menorah (a seven-branched candelabrum), reflecting Jewish religious themes. Famous mosaics include those from Sepphoris and Hamat Tiberias.

Architecture

Roman Architecture

Roman architecture in Judaea was characterised by its use of innovative building techniques, including the widespread use of concrete, arches, and vaults, which allowed for the construction of large, durable structures like aqueducts, basilicas, and amphitheatres. It emphasised grandeur, functionality, and symmetry, with iconic buildings such as the Colosseum, Pantheon, and Roman Forum reflecting the Roman Empire’s engineering prowess and aesthetic ideals.

Jewish Architecture

Jewish architecture in Roman-Judaea was primarily centred around religious structures like synagogues and the Second Temple in Jerusalem, with a focus on simplicity and modesty, avoiding the use of images or idols. While synagogues often featured open prayer halls with mosaic floors and simple layouts, the Second Temple, expanded by King Herod, was an imposing structure with courtyards, gates, and intricate stonework, reflecting a fusion of Jewish religious tradition and the architectural influence of the Roman Empire.

Herodian Architecture

Herodian architecture is the architectural style and building projects commissioned by King Herod the Great during his reign over Judaea (37–4 BC). Herod sought to leave a lasting legacy and solidify his rule by combining Roman architectural innovations with traditional Jewish styles, resulting in grand, monumental structures. His constructions were known for their scale, sophistication, and advanced engineering techniques.

Fashion

Fashion in Roman-Judaea reflected a blend of Roman influence and Jewish traditions, with variations based on social status, region, and religious observance.

Roman Clothing

Roman men commonly wore tunics, which were simple, knee-length garments, with the elite also donning togas, a large, draped cloth symbolising their citizenship and rank. Sumptuary laws regulated who could wear specific materials or colours, such as imperial purple, reserved for the emperor and the highest elites. Women wore stolas, long dresses often belted at the waist, accompanied by broaches, shawls draped over the shoulders or head. Clothing was made from wool or linen, with wealthier Romans using finer fabrics like silk.

Religious leaders in Rome, particularly priests and priestesses, wore clothing that symbolised their sacred duties and the deities they served. Male priests, such as those of Jupiter (flamines), wore the apex, a conical cap with a spike, and a toga praetexta, a white toga with a purple border, signifying their religious status. Priestesses of Vesta were dressed in long, modest white gowns with a special head covering called the infula, adorned with woollen bands, representing their purity and devotion.

Jewish Clothing

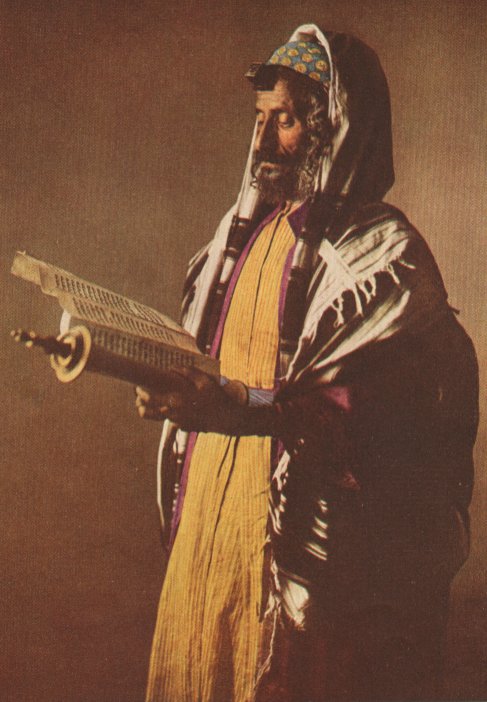

Religious observance of Jewish dietary laws and modesty often led to more conservative and practical attire. Women typically wore long dresses or tunics with head coverings, while men wore simple tunics with fringed prayer garments (tzitzit) to fulfil the commandment in the Hebrew Bible’s Numbers 15:38. Men in the first century often covered their heads during prayer or religious rituals, usually with a shawl or a cloth, as a sign of reverence to God.

Jewish priests wore elaborate, symbolic garments prescribed by the Torah, including linen tunics, sashes, and turbans, with the High Priest wearing additional sacred items like the Priestly breastplate with 12 different gemstones representing the 12 Tribes of Israel in the Hebrew Bible.